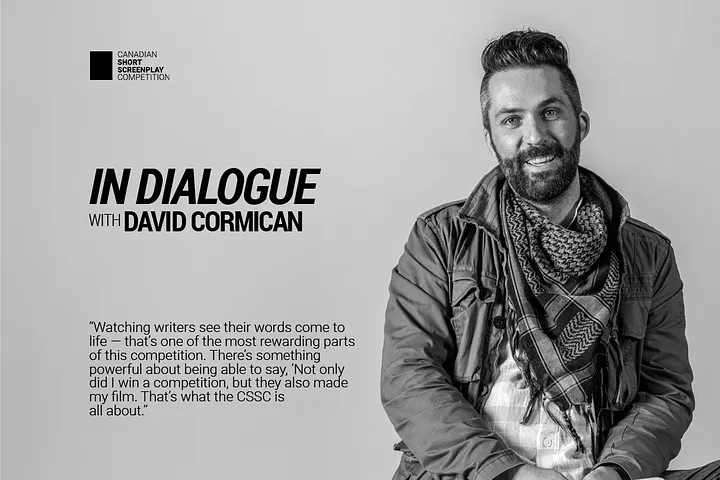

If you’ve ever wondered what it takes to make it in the film and television industry beyond the glitz and the grind, David Cormican has a story for you. A self-described “underemployed actor-turned-producer,” Cormican’s journey is equal parts tenacity, timing and the ability to turn obstacles into opportunity.

We sat down with the prolific showrunner, producer and founder of the Canadian Short Screenplay Competition (CSSC) and talked about how his winding creative path led him to become a champion of emerging screenwriters and why now was the perfect time to bring the CSSC back to life.

Cormican didn’t grow up with dreams of Hollywood. In fact, his first taste of performance came when his high school crush asked him to audition for the Frederick Loewe and Alan Jay Lerner Tony Award-winning musical, Camelot. He landed a small part in the school production; not Lancelot, but “Third Knight on the Right (aka Sir Colgrevance).” The experience hooked him so much so that he pivoted away from his plans to become a police officer and dove headfirst into acting.

After drama school at Grant MacEwan Community College (now MacEwan University), he worked with Alberta Opera and studied in Ireland at the Gaiety School of Acting. His summers were filled with creative exploration, but film called to him in a different way. After training at the New York Film Academy, Cormican set his sights on a more lucrative film centre, landing not in the city where dreams are made (NYC), but where dreams are constantly under construction (Toronto).

While chasing auditions, he sustained himself through brand ambassador and marketing gigs. “I was making decent money,” he recalls. “Enough to start funding my own projects and attending festivals like TIFF and Banff.” But acting roles weren’t fulfilling him creatively. “I was getting frustrated with the kinds of parts I was being sent out for,” he says. “So I (naively) started writing the kinds of roles I wanted to play.”

That decision changed everything.

As a self-starting writer, Cormican realized something quickly: scripts simply don’t produce themselves. So he leaned into producing; at first pretending, then doing. “I was forced (through necessity) to become a producer,” he laughs. Armed with his own concepts, scripts and even some of his friends’ projects, he began networking, pitching and learning the business by living it.

His short-form series Crazy People (later renamed Committed during a development deal), landed him a runner-up status in the very first Just for Laughs Just For Television comedy series pitching forum, his very first set of coverage in Variety and five option and purchase agreements on offer. Though the show ultimately never made it to air, it was a turning point for Cormican. “That was the moment where everything shifted,” he says. “Suddenly, I had a literary agent. I was a producer. Even if I knew nothing.”

It also led him to Kevin DeWalt of Mind’s Eye Entertainment, who would later offer him a full-time role as head of development overseeing the company’s robust feature film slate, despite Cormican’s humble protest that he was still, “just an actor pretending to be a producer.” Kevin didn’t laugh. He hired him.

Cormican committed to living in the City of Regina for what he thought would be a short stint.

He stayed four years.

During his time in Saskatchewan, Cormican founded the Canadian Short Screenplay Competition. It was, in many ways, a creative response to gaps he saw in the industry.

“I skipped some steps early in my career. I was exec’ producing multi-million dollar movies with major Hollywood stars, but I didn’t have that line producer, boots-on-the-ground experience,” he says. “The CSSC was a way for me to get that — and to identify new talent.”

The concept was simple but powerful: screenwriters from around the world submit short scripts. A jury ranks them. The top three win. And most importantly, one of the winning scripts gets made into a film.

“There are hundreds of screenwriting competitions,” Cormican says. “But very few of them actually make the winning script(s) into a real film. That’s where the CSSC stood out, and still does.”

The competition led to the creation of films like Rusted Pyre, which went on to premiere at Cannes and win many awards; but only after getting Cormican kicked out of the National Screen Institute. “It was devastating at the time,” he says, “but it lit a fire. I needed to prove we were the team worth betting on — not sending home!”

While the CSSC incubated emerging voices, Cormican’s own producing slate was growing exponentially. His breakout television series Between was the first original Canadian series picked up by Netflix — a landmark moment for the Canadian television industry.

“There were no playbooks for deals like that at the time,” he remembers. “We were launching alongside House of Cards. It was surreal.”

From there came co-productions like Tulipani, Love, Honour, and a Bicycle which premiered at TIFF, and the international Emmy-nominated Tokyo Trial, a co-venture spanning Canada, Japan, Lithuania and the Netherlands. That project, he says, was one of the hardest and most rewarding of his career.

“We set our North Star early; we said we were going to go for an International Emmy Award. That meant everything had to be perfect: lighting, costumes, everything — And we got nominated.”

Eventually, the CSSC went on hiatus. Cormican had moved back to Toronto and co-founded DCTV with Academy Award-winning producer, Don Carmody. With a greenlight on Between and other major projects looming, he simply couldn’t maintain the competition at the level it deserved.

“I didn’t want to do it half-assed,” he says. “So we shelved it. But it has always been in the back of my mind.”

The spark to relaunch came unexpectedly, when an intern, asked him point-blank:

“Whatever happened to the CSSC?”

At first, Cormican shrugged it off. But the question lingered. He had also been speaking to a friend, a short filmmaker and Oscar winner, who reminded him how beautiful short films are.

“There’s something pure about short films. It takes us back to why we started making films (and series) in the first place.”

So, he decided: the CSSC must return.

Today, the CSSC is back, and it’s bigger than ever. With an international reach, a new cohort of writers and collaborators, and renewed commitment from Cormican, the competition is on track to produce a new wave of winning scripts.

One past CSSC-winning script is already in post-production, boasting an all-star cast that includes Game of Thrones’ Owen Teale, Gosford Park’s Sophie Thompson and rising young talent Leo Harris (The Count of Monte Cristo). “The writer, Neil Graham, even got to visit the set,” Cormican shared.

“Watching writers see their words come to life — that’s one of the most rewarding parts of this competition.”

Cormican is also in talks with financiers about producing a slate of short films from the CSSC archive. “We’ll start making them in threes or fives,” he says. “Make some noise. Launch some careers. Pave the way for the new generation of Sorkins through this competition.”

For Cormican, it all comes back to giving writers a real shot.

“There’s something powerful about being able to say, ‘Not only did I win a competition, but they also made my film,’” he says. “That’s what the CSSC is all about.”